It’s past time for Britain’s Labour opposition to get its act together about cannabis.

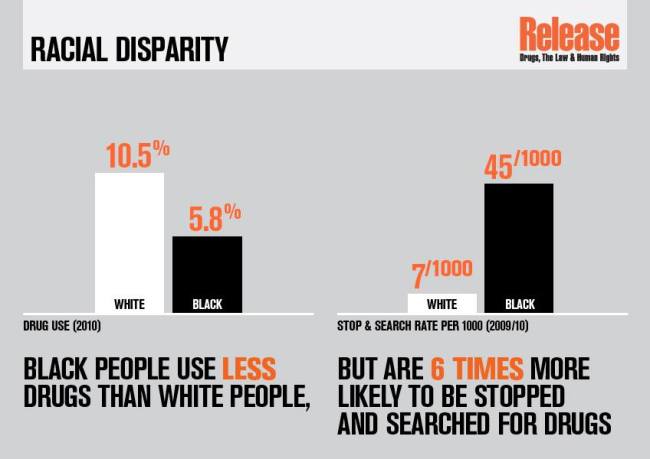

If you’re black and going about your day in England and Wales you’re 6.3 times more likely to be stopped and searched by police, a new report from Release and LSE revealed this week. Guns and knives are the focus of only a fraction of these searches: most are for low level drug offences, above all cannabis. And despite government figures suggesting use of the herb is significantly lower among black people than among whites, in some areas, such as Dorset, being black makes you 17 times more likely to be stopped. Get caught in possession of cannabis in London and the likelihood of then being charged multiplies 5 times. In the US, the arrest ratio of blacks to whites is just three to one, less than half that for the UK.

Looked at from the perspective of Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking work on America’s War on Drugs, The New Jim Crow, these statistics, shocking in their own right, also beg the question of what exactly British cannabis policy is intended to do. Should we take the government at its word and assume that the purpose is above all to ‘safeguard’ the nation’s mental health from the scourge of ‘skunk’? Or is Michelle Alexander closer to the truth when she argues that drug policy is part of a coercive system of social control, one that primarily targets marginal groups and minorities? British Asians, for example, are 2.5 times more likely to be stopped. Just the last 12 months have seen more than half a million people stopped and searched for drugs – one person every 58 seconds. The arrest rate is a mere 7%.

Skunk, ostensibly the prime target here, is the generic term preferred by politicians and hacks for modern, intensively bred hybrid strains; the idea being that these new forms of cannabis are of unprecedented and dangerous potency. There are obvious holes in the skunk myth: the government’s latest figures, for example, state that it has on average only a percent or so more THC than traditional imported herbal cannabis (14%, as opposed to 12.5%). Even taken on its own terms, the war to rid the nation’s streets of this alleged evil has been lost in spectacular fashion: over the course of successive New Labour governments, amid endless blithering about its dangers, skunk took the UK by storm, forcing out the supposedly safer staple of traditional Moroccan hash, until in the space of barely a decade the pungent menace came to account for around 80% of cannabis consumed in the UK.

Successive British governments have been getting it badly wrong on the issue of cannabis. And the Labour Party, now drifting in opposition under Ed Miliband, can take the largest share of the blame for that. Across the Atlantic things look very different: the leader of Canada’s opposition Liberal Party, Justin Trudeau, has just admitted to smoking cannabis while an MP and has subsequently surged ahead in the polls. Earlier in the summer, Trudeau announced his support for reforming Canadian cannabis laws. He now leads at 38% to the Harper government’s 29%. Canada has recently been tipped by Ethan Nadelmann, along with the Netherlands, as a country likely to be the next to ‘legalise’. South of the border this year alone cannabis reforms of one kind or another have passed in Oregon, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, Hawaii, Maine, Vermont, and Nevada. Colorado and Washington, which are now celebrating Eric Holder’s historic Thursday memo, will be joined later in the year by Uruguay.

Like Canada, the UK is ripe for change—and far more so, in fact, than a country such as Uruguay. An Ipsos Mori poll in February this year reported that 53% of the public supports legalisation. Cannabis can be found in every walk of British life, every strata and subculture—not least among politicians. David Cameron and Boris Johnson have admitted to past use, either of ‘pot’ or ‘harder drugs’. A Sun investigation last month found that toilets in the House of Commons appear to be routinely used for sniffing cocaine. With politicians and the public all either high or on side, there seems little reason for Miliband not to follow Justin Trudeau’s lead. But more likely Britain will be stuck with the Ed Miliband who leapt to criticize former police officer and Home Office minister Bob Ainsworth when he called for cannabis decriminalization. ‘Honest Ed’ can be seen here smilingly gormlessly as he is photographed beside a grinning, red-eyed student, seemingly oblivious to the fact that the student is high and has in his hand a gigantic green bong.

Labour’s history with cannabis is less than heroic. Terrified of the issue, the Conservatives’ law and order credentials, and the right wing popular press—above all the Daily Mail—they have ended up out-nastying even the Tories. Reacting to hysteria drummed up around the issue of skunk and mental health, Labour forced through more prohibitive laws and granted yet greater police powers. How exactly a move such as Gordon Brown and Jacqui Smith’s 2008 reclassification to Class B was going to protect anybody’s mental health was never explained, beyond the fact that it was important, in Jacqui Smith’s words, to ‘send a message’. What, we are left wondering after the report from LSE and Release, was the message that Jacqui Smith wished to send? In the absence of other compelling evidence, you could be forgiven for thinking it was ‘don’t be black in Dorset’.

Back in 2002, a Labour government came within a hair’s breadth of decriminalizing the use of cannabis. Home Secretary David Blunkett planned a downgrade to Class C, a move which, with the way the law stood at the time, would have put an end to all criminal charges for possession and removed from the police the power of arrest. As far back as 1981 experts on the government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) had been recommending reclassification for this very reason, and Blunkett’s proposal could claim the support of a mountain of favourable reviews that had been commissioned by the Department of Health and the Home Office. In May, the Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC), on which current Prime Minister David Cameron then sat, gave its backing; and by July, with a solid consensus established among legislators, experts, and the various advisory bodies, the Home Secretary was able to announce that cannabis would be reclassified within the year. The weed was about to be freed. Or rather the millions of British people each year who make an informed choice to enjoy it were.

No civil libertarian, Blunkett was not on an ideological crusade to liberate British cannabis enthusiasts from state oppression. Instead, the New Labour rhetoric was all about resources. Just after entering office in June 2001, he had met with Brian Paddick, a Commander of the Metropolitan Police in charge of Lambeth. The next month Paddick embarked on a policy of instructing officers in the south London borough, which includes Brixton, not to arrest people found carrying small quantities of cannabis; with officers left to judge what exactly a small quantity was. Paddick, like the then Home Secretary, is no radical, and stressed that when in charge of other stations where his resources were less stretched he would instruct his men to enforce the law. This was consistent with Blunkett’s professed desire to free up police time to focus on more harmful controlled drugs, pursue traffickers and pushers, and tackle violent crime. All of which makes clear that the reforms proposed in 2002 ‘should be seen more as attempts to impose central control over the behaviour of officers on the ground’, as James Mills argues in Cannabis Nation, ‘rather than efforts to radically depart from previous policies.’

Yet Blunkett hit a wall of resistance. Catching wind of the reclassification announcement, as Paddick explains, ‘at the last minute, Mike Fuller, then a DAC in the Met with responsibility for drug policy, and Ian Blair, then deputy commissioner, went and saw Blunkett and convinced him to retain the power of arrest.’ Where he had intended for the downgrade to be a bold assertion his authority, the Labour Home Secretary now found himself squaring up with the police. They weren’t impressed, and he swiftly beat a retreat.

In the end, cannabis did become a Class C drug, and the law came into force in 2004. But an amendment to to the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) made possession of a Class C Drug an arrestable offence in 2003, and the maximum possible sentence for supply was increased: ‘the purpose of the reclassification of cannabis to Class C, which was to ensure that possession was not an arrestable offence, was further undermined by the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act of 2005’, Mills explains, ‘This was a wholesale rationalisation of the law which deemed that all offences could be arrestable provided that the arrest is necessary and proportionate to the circumstances. In effect this represented a further extension of police discretion.’

Blunkett’s downgrade came into law in 2004 and Labour came under renewed attack from the right wing popular press and the Tories. David Davis, in keeping with a party tradition, was the first to bring skunk to the House of Commons in January 2005, amid a welter of headlines such as Melanie Phillips’ ‘Cannabis caused a 14-year-old to kill. Yet still they say it’s harmless.’ Questioned bluntly by Robert Jay QC at the Leveson Inquiry in June 2012 as to whether he had been making policy to ‘appease the Daily Mail’, Gordon Brown denied that and replied: ‘on cannabis, you know, I don’t hold what is probably the more conventional view about the effects of soft drugs, so I was against the reclassification of cannabis and in fact we reclassified it back. These are views that I hold personally and I hold them quite strongly and I may say that probably I used my position to persuade members of the government who were not as keen on that policy as I was.’

Obsessed and cowed by the Mail in equal measure, Brown had set about consolidating the marginalization of the ACMD immediately he took office in June 2007. Home Secretary Jacqui Smith requested that the scientists review cannabis classification ‘in the light of real public concern about the potential mental health effects of cannabis use and, in particular, the use of stronger strains of the drug’. In a desperate attempt to drum up some popularity with demographics that still bother to vote, cannabis policy was being cordoned off in a safe, science-free zone by the Labour government. Preempting the ACMD review of reclassification four months before it was due, senior Whitehall figures let it be known to the press in Jan 2008 that, even before it was offered, the ACMD advice was going to be dismissed. As part of this carefully orchestrated move, the Chief Political Correspondent of The Times wrote: ‘Cannabis is to be reclassified as a Class B drug after an official review this spring, The Times has learnt. Gordon Brown and Jacqui Smith are determined to reverse the decision to downgrade the drug when the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs completes its report in the next few months. While its recommendations are not yet known, ministers are already making plain that the Home Secretary is prepared to overrule the expert body if necessary.’

The Chair of the ACMD, Professor David Nutt, wrote in the review, which was issued on May 7th 2008, that following ‘a most careful scrutiny of the totality of the available evidence’: ‘the majority of the Council’s members consider– based on its harmfulness to individuals and society– that cannabis should remain a Class C substance’. This was rejected outright by Jacqui Smith, who explained to MPs the same day that ‘my decision takes into account issues such as public perception and the needs and consequences for policing priorities’.

The ACMD was cast out into the wilderness. Brown, who had just led his party to a comprehensive defeat at the local elections, got the ‘crackdown on cannabis’ stories he so desperately needed. As for the faceless masses on the receiving end of British policing, they were already criminals. Reclassification to Class B now meant the added threat of increased prison sentences for possession. Stop and searches—nearly all under PACE and related legislation—had begun back in 2001. They went on to hit a ten year peak in 2010/11 at 1.3 million. That same summer rioting exploded across England, two days after Mark Duggan was shot dead by police on a curb-side outside Tottenham Hale station—the trigger coming when, it is alleged, officers at a protest on August 6th forcibly restrained a sixteen year old girl. Burning and looting spread from North London to Bristol, Birmingham, and Manchester. The Guardian’s Reading the Riots investigation concluded: ‘Although rioters expressed a mix of opinions about the disorder, many of those involved said they felt like they were participating in explicitly anti-police riots. They cited “policing” as the most significant cause of the riots, and anger over the police shooting of Mark Duggan, which triggered initial disturbances in Tottenham, was repeatedly mentioned—even outside London.’ Outside observes like Professor Gus John from the University of London drew the same conclusions.

If there is a real danger to the public here, then it appears to be coming from the law. Criminalising cannabis use is serving no good purpose. The continued institutional resistance to reform is genuinely hard to comprehend. There are some, like Stuart Hall or Michelle Alexander, who view drug laws as part of a coercive state architecture, a form of social control that has been built up since the west was last shaken by economic crisis in the ‘70s. Others, like Rowan Bosworth-Davies, chair of LEAP UK, share the outrage yet look for more pedestrian explanations such as a drive for measurable policing statistics coming out of the Home Office. In this former Met detective’s view the root cause of the problem is the constant push for meaningless numbers by deskbound control freaks, the ultimate effect of which has been to politicise British street policing and wreck its original purpose (that of Sir Robert Peel and the first Commissioners.) Or there is Professor Charlie Beckett, a media specialist, who analyzes the failure of Bob Ainsworth to do anything about cannabis while a Labour Minister at the Home Office and—noting that most senior officers want the law changed—lists three key obstacles:

- Civil servants who would only advise within pragmatic policy parameters

- The top politicians in his government who would see it as risky and a distraction

- Government spin doctors who would see it as handing ammunition to the right-wing newspapers

‘What is really stopping this happening’ Beckett adds ‘is the media and specifically the right wing popular press.’ The BBC surely also deserves special mention.

Reform is moving apace elsewhere while Britain panics and stagnates. New York is finally beginning to extricate itself from ‘Stop and Frisk’, an evil twin to ‘Stop and Search’, after Judge Shira Schiendlin ruled that the program is racist. Noting that 80 per cent of those stopped were either black or Hispanic, and that roughly 90 per cent of these people were not charged with any crime, Judge Schiendlin argued that the city had ‘adopted a policy of indirect racial profiling by targeting racially defined groups for stops based on local crime suspect data’. She added, ‘I also conclude that the city’s highest officials have turned a blind eye to the evidence that officers are conducting stops in a racially discriminatory manner.’ Judge Schiendlin found points in the system at which to point the finger of blame.

But the New Jim Crow view is that to fully comprehend New York’s ‘Stop and Frisk’ its lineage must be traced beyond the massive expansion of drug war policing under Reagan back to the dark days of the Nixon administration. It is here, arguably, that the War on Drugs as it functions today was first conceived and refined. Two jailed players in the Watergate Scandal, John Erlichman, White House counsel to Nixon, and Bob Haldeman, his Chief of Staff, left in their memoirs frank admissions about just how the drug war was designed to work. Ehrlichman wrote, “Look, we understood we couldn’t make it illegal to be young or poor or black in the United States, but we could criminalize their common pleasure. We understood that drugs were not the health problem we were making them out to be, but it was such a perfect issue… that we couldn’t resist it.” And Haldeman gifts us a particularly choice line: “[Nixon] emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to.”

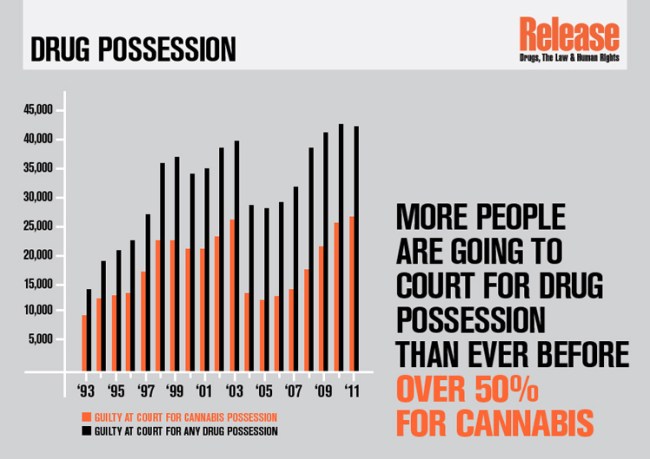

With such admissions, and the deafening silence from the opposition, it is disturbing to look at Britain today through the lens of The New Jim Crow. There are Labour MPs who have spoken out in favour of decriminalization in the past, like Diane Abbott, MP for Hackney North and Stoke Newington, a constituency which saw its fair share of rioting. But as yet Diane Abbott has said nothing about the report from Release. Recently she seems to have been more busy worrying about the risks of skunk. Meanwhile prosecutions for drug possession in England and Wales have hit an all-time high. This is being driven primarily by cannabis prohibition. In the last 15 years, writes Niamh Eastwood of Release, ‘we have criminalised approximately a million people in England and Wales for simple possession of a drug. Of those million, well over 50% were criminalised for cannabis possession.’

The Labour Party needs to get its act together about cannabis. There is a shameful legacy to be undone. It’s time for Ed Miliband to take a leaf out of Justin Trudeau’s book, even if he won’t take a toke on the spliff.

—

Most quotations from British sources are taken from Cannabis Nation: Control and Consumption in Britain, 1928 – 2008 by James Mills. American ones are from The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander.

Reblogged this on cannabisforautism and commented:

If nothing else, the war on drugs must end because no one is capable of waging it indiscriminately enough and it’s starting to look really embarrassing.

Reblogged this on The Cheetah-Chottah Press and commented:

Thought this one was worth reblogging

Reblogged this on PNVP.Org | Peace & Non-Violence Project and commented:

Thank you TheRealSeedCompany!

If nothing else, the war on drugs must end because no one is capable of waging it indiscriminately enough and it’s starting to look really embarrassing.