A classification of endangered high-THC cannabis (Cannabis sativa subsp. indica) domesticates and their wild relatives is an essential new study from John McPartland and Ernest Small, published April 2020. Since Small’s Cannabis: A Complete Guide, this is the first authoritative work to address the dire situation for Cannabis biodiversity.

McPartland and Small’s focus is indigenous Central and South Asian varieties of subsp. indica. These face imminent extinction. Preservation in genebanks is urgently needed. The authors’ case is that classifying subsp. indica varieties is more than a mere dry academic exercise—that formal recognition can enable decisive action.

Their new taxonomy rests on an analysis of 1100 specimens in 15 herbaria. It splits the old two-part Small and Cronquist lumper taxonomy for subsp. indica into the following four-part system:

- Cannabis sativa subsp. indica var. indica = South Asian domesticates (“landraces”), informally ‘Sativas’

- Cannabis sativa subsp. indica var. himalayensis = Wild-type South Asian populations

- Cannabis sativa subsp. indica var. afghanica = Central Asian domesticates (“landraces”), informally ‘Indicas’

- Cannabis sativa subsp. indica var. asperrima = Wild-type Central Asian populations

“Recognizing [these] infraspecific taxa helps to identify populations vulnerable to extinction”, explain the authors. Irreversible loss of biodiversity is occurring through introgressive hybridization (“the infiltration of genes between taxa through the bridge of F1 hybrids.”) Most critically in need of preservation are the wild-type varieties, var. himalayensis and asperrima.

Troublingly, however, according to Genesys, of some 1400 Cannabis accessions in global genebanks, as few as five could be from subsp. indica. Hopefully, this worryingly low number may be partly explainable by genebanks not applying this taxon to their material rather than a lack of material per se. But there is no doubt that the few large genebanks with good stores of Cannabis germplasm have low to no representation of subsp. indica types, still less of authentic landrace and wild-type populations.

As a side note, worth emphasizing if you’ve spent decades caught up in the Cannabis nomenclature nightmare is that the informal classifications ‘Indica’ and ‘Sativa’ can be used accurately to refer to some authentic Asian landraces, though not to describe modern hybrid slop. Notable also is that many landraces appear to have arisen as hybrids between var. indica and afghanica, certainly in the centuries immediately prior to the Hippie Trail era and perhaps as far back as the thirteenth century or earlier.

Turkestani var. afghanica collected in Xinjiang by Frank Meyer, a germplasm collector for the US Department of Agriculture, Nevada, c. 1912

I’d argue that McPartland and Small understate the extent to which Asian subsp. indica landraces and wild-type populations are endangered. They relay a few anecdotal examples of introgression involving foreign seed being brought to historic centres of cultivation and biodiversity in the ’70s to ’90s. But they make no mention of the rise of Internet commerce, which today presents the gravest danger. The shipping lists of the average Amsterdam or UK Internet ‘seed bank’ would make for horrifying reading now that online retail is arriving in South and Southeast Asia. The largest Amazon campus in the world has just opened in Hyderabad. An unprecedented influx of hybrid seed into Asia is already underway, and it’s only a matter of time before the corporate behemoths get their teeth sunk in to what, historically, was the world’s largest market for Cannabis products.

In essence, what we’re faced with now is Western hybrid slop surging eastward like a tidal wave, wiping out many millions of years of biodiversity, permanently.

McPartland and Small are clear that their current study is provisional—an opening salvo. And as Small himself has emphasized, taxonomy is both a theoretical science and a practical art—one that can be repeatedly revised. In that light, I’d note that I have questions concerning how precisely their new classification brings into focus certain crucial regions and populations. To my mind, their treatment of the Himalaya raises questions. Questions, primarily, because I’m not a botanist or a taxonomist. So back up a truck-load of salt with which to take what follows.

Himalaya: I suspect further splitting may be in order—in other words, that typical Himalayan landraces could be classified as a separate taxon from var. indica. With that, I have doubts about var. himalayensis as defined in the current taxonomic key.

The shortcomings of the study as regards the Himalaya appear mostly to be due to available herbarium specimens not being adequately representative. That said, the historical and modern accounts of Himalayan Cannabis on which the study relies can also be quite misleading. There’s a long-standing tendency to claim that Himalayan charas is harvested from wild plants. It can be, but these wild-growing (rather than truly wild) populations yield an inferior product known as “jungli”, which sells at a fraction of the price of charas from cultivated fields. An essential Victorian document, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (IHDC) is clear on this distinction and it remains the case today.

Multipurpose Himalayan landraces, northern Kumaon, 2015. The region had experienced low rainfall during monsoon.

The study, in my view, misrepresents how the main Cannabis plants harvested in the Himalaya were and are undoubtedly landraces. These traditional alpine domesticates are markedly distinct from the var. indica type of the rest of India, meaning the region south of the Himalaya (excluding Punjab and Sindh). Yes, it is true that wild varieties of some species of plant can be sown as a crop. But typical cultivated Himalayan Cannabis plants are certainly domesticates, albeit part of crop–weed–(wild?) complexes. As McPartland and Small state—though of their wild-type variety, var. himalayensis—these cultivated fields are harvested for “bast fiber (stalks), bhāng (leaves), hand-rubbed charas (hashīsh), or achenes (seeds).” More accurate would be “and seeds”. Nothing is wasted in the alpine Himalaya, because nothing can be wasted. Large leaves unsuitable for bhang or charas production are often used as a vegetable (“sabzi”).

But this is about more than mere traditions of use. In Kumaon— which the IHDC rightly takes to be representative of Himalayan Cannabis botany, culture, and economies—typical seeds are markedly large. This is the case continuing eastward through Nepal to Kathmandu. Seeds of landraces from the Dhorpatan region of Midwest Nepal are some of the largest I have seen, like marrow fat peas, comparable to those of Chinese hemp landraces. This is undoubtedly evidence of domestication for use as food. Cannabis seeds are an essential source of protein and fat in the Himalayan diet, as is also the case in regions of the Hindu Kush such as Chitral.

Similarly, these crops’ high levels of bast fibre (which, again, the study understands to be a trait of var. himalayensis) surely relate to these Himalayan landraces being selected over millennia for use as rope and textiles. Historically, the Khas (Pahari) castes of the alpine Himalaya—then, as now, the people who cultivate Cannabis—wore “hemp” clothing, which was taken as a mark of their low status in the excruciatingly stratified Hindu social system. In Pahari villages, the fibres continue to be a crucial source of rope for tethering livestock, though their use for textiles is being revived, largely driven by Western demand, and sometimes they are sold to traders for industrial uses. Likewise, Himalayan domesticates are exceptionally tall, given good conditions hitting well over four metres.

My guess—though it is nothing more than a guess—is that further study will show the typical ratio of THC to CBD in Himalayan landraces to be closer to that of Central Asian domesticates. Their aromas are distinctive also; which is to say, their total phytochemical profiles may also mark them out from var. indica ganja landraces and Central Asian populations.

In other words, a combination of morphological and phytochemical characteristics could well be defined to separate Himalayan domesticates reliably as a distinct formal variety, as is necessary in conventional plant taxonomic identification keys.

In following the misleading “wild mountain Cannabis” trope, the study inadvertently distorts some of the better historical sources such as the IHDC. In Table S4, it’s purported that the IHDC states Urgam, Almora, and Kullu are regions where charas is only harvested from wild plants. In fact, the IHDC merely reports this of Urgam, a valley in the Garhwal Himalaya. The Victorians were probably correct on this point, but only in so far as in Urgam some charas is harvested from jungli stands, as is the case throughout the Himalaya. I have visited Urgam twice, and the roadhead is a point from which cultivated charas from surrounding valleys is exported. Most Garhwali charas today is produced from domesticates, as it almost certainly was in the past. Importantly, the IHDC records that the bulk of charas from Almora and the rest of the Kumaon Himalaya (which sold at several times the price of that from Yarkand) was in fact harvested from cultivated fields. For Kullu, then part of the Native States neighbouring the Punjab Himalaya, the IHDC states as follows:

“There is more or less evidence of cultivation of the [Cannabis] plant all over the Himalayan portion of the province, including the smaller Native States. The cultivation is in small patches. A report from Kulu in 1880 says: ‘Almost every house has a small patch near it, a long strip beside a hedge, or a small bed a few square yards long (sic) in area.’ The only other detail of cultivation furnished is that the season of growth is from April and May to October and November. It may be safely assumed that the method of cultivation does not materially differ from that practised in Kumaon, which has been fully described.”

Ostensible var. himalayensis traits such as high bast fibre appear to be signs of these wild-type plants being part of crop–weed–wild complexes. Essentially, across northern India from Manipur westward through the alpine Himalaya and north of the Ganges, all the way through Punjab and up into the Hindu Kush and Pamirs of Central Asia, Cannabis exists as one big crop–weed–wild complex.

Wild-growing var. himalayensis, northern Pakistan. Photo by Landrace Genetics, 2019.

If a pristine aboriginal var. himalayensis population is ever found that’s unaffected by domesticates, perhaps in Arunachal Pradesh or some remote corner of Burma, I strongly doubt it will show a markedly high ratio of THC to CBD or high levels of bast fibre.

My guess is that Himalayan landraces are representative—in practice, if not necessarily genetically—of a millennia-old Central Asian tradition of multipurpose use that long predates ganja, a comparatively recent South Asian innovation for which true var. indica landraces were domesticated.

Indian botanists have long wondered whether the northern Iranian-speaking Central Eurasian nomads known as the Scythians brought Cannabis cultivation south to the Indian Himalaya. Based on accounts of the Pontic Scythians by Herodotus (c. 440 BCE), it seems likely that Scythian Cannabis was a multipurpose crop. It was certainly notably tall, used for textiles (as fine as the best European linen, says Herodotus), smoked by means of fumigation, and – at very least on the western steppe – drunk in beverages with opium. It’s highly likely it was also cultivated for food use. Current studies on Central Asia are revealing how nomadic cultures were inextricably involved in cultivation, and Scythians themselves spanned settled agricultural and urban communities such as Shache (Yarkand) to true nomads such as the Royal Scythians, a point this study overlooks. We now know that around 500 BCE the first unequivocal evidence of utilization south of the Indus appears in the Uttarakhand Himalaya in the form of a sudden unprecedented rise in pollen at a retting lake in Garhwal. This is not unlikely to be connected to economic changes brought about by the Achaemenid conquest of northwest India under the Persian Emperor Darius I, who subdued the eastern Scythians in 518 BCE, brought them south to India as the core of his war machine in 515 BCE, and stationed them across the newly conquered territories as part of Persia’s satrapies.

Whether production of fibre in Garhwal was merely answering demand from the Achaemenids, actively instigated by their Scythian military, or begun by other Central Asian Scythian-like tribes fleeing the new empire, we will never know. Perhaps it was none of these things. But notably, in Nepal today, some Khas (i.e., Pahari) communities claim descent from Central Asian nomads and much like the Royal (i.e., ‘Aryan’) Scythians, refer to themselves as ‘Khas Arya’, a subject I looked at in an earlier post here. Relatedly, all the Pahari dialects such as Garhwali, Kumaoni, and Nepali probably developed independently of other Indo-Iranian languages of lowland India from a separate northern branch of Khas Prakrits following the Achaemenid era.

Suffice to say, my guess is that the earliest Central Asian subsp. indica domesticates were multipurpose plants, and that var. indica and afghanica—true Sativas and Indicas—are comparitively recent specialized creations associated, respectively, with the custom of smoking ganja with tobacco and the significantly older (probably pre-850 CE) Central Asian practice of sieving resin glands through silk to make charas.

Ganja & Bhang: If all this is getting too speculative for your tastes, then strap in, because what follows deals with the dating of ancient Indian texts, which is a notoriously imprecise and arbitrary business.

Based on what little circumstantial evidence is available, it would appear that true var. indica domesticates, i.e. ganja landraces, diffused across South and Southeast Asia in conjunction with the popularization of tobacco smoking and cultivation. This would fit with the earliest dates for the term ganja, which could be as early as circa twelfth to fifteenth century, but is more probably circa sixteenth century. Tobacco shot to popularity in South Asia in the early decades of the seventeenth.

The Ānandakanda, a Nath Shaiva compendium on alchemy, is the earliest text to describe the rogueing process through which ganja is produced – in other words, the so-called “sinsemilla technique”. G. K. Sharma, a botanist, speculated the text may date from the tenth to thirteenth centuries. But G. J. Meulenbeld, a scholar of Sanskrit and Indian medicine, argues that the Ānandakanda postdates the thirteenth century and gives the presence of the term ganja as evidence for that. “The name gañjā appears for the first time in the sixteenth century,” he notes, “in the Bhāvaprakāśanighaṇṭu and Ṭoḍaramalla’s Āyurvedasaukhya.” Recent studies also indicate that a text by the Kashmiri scholar Narahari Pandit, in which the term ganja appears, very likely dates not to the thirteenth century, as claimed in the IHDC, but to the seventeeth century.

Bengali var. indica: ‘Ganja plant almost ready to cut, Naogaon’. IHDC, 16th February 1894

Traditional Asian terminology for subsp. indica is seamless and fluid, which can confuse the uninitiated. Bhang can mean the subsp. indica plant and all its products, whether cultivated or wild and whether charas, ganja, or leaf, or any preparation thereof. But more narrowly, bhang is a distinct type of crop and its specific product (in practice, crude seeded inflorescences and small leaves) such as still cultivated under license in India at sites like Hoshiarpur at the foothills of the Himalaya in the Punjab. From there, the product bhang is exported to regions such as Rajasthan. Historically, Punjab has only been a bhang producing region, in part due to Sikh culture. By contrast, from Uttar and Madhya Pradesh eastward and southward, cultivation has in recent centuries focused on ganja, a more sophisticated crop and product, sown and harvested at different times, and requiring significant skill to raise. Importantly, while ganja can be called bhang, bhang—in the narrow sense—cannot accurately be called ganja.

Ganja first appears in English in the work of a merchant, Thomas Bowrey (1659–1713), who also has the honour of providing us with among the first English-language accounts of getting stoned. Earlier colonial accounts of Cannabis such as Garcia de Orta’s from Goa, southwest India, mention only the term bhang and say nothing of smoking. Bowrey had extensive experience of Bengal, the Coromandel Coast, and Sumatra. Like Herodotus, he’s proved to be a strikingly reliable witness. This is to be expected. He was in Asia to make money through trading commodities. According to Bowrey, bhang was cultivated throughout the Coromandel up to Bengal, but ganja was an imported product and was shipped to India from “the Island Sumatra”, where Bowrey himself lived for several years at Achin (i.e., Aceh) and engaged in this ganja trade. What seems most likely is his comments concern only commercial cultivation and that ganja was a household or small-scale crop in eastern India. According to contemporary Acehnese, Cannabis itself was introduced to Sumatra by Indians, probably Telugus, who may well have dominated cultivation and export of ganja. Naths themselves had strong links to the region.

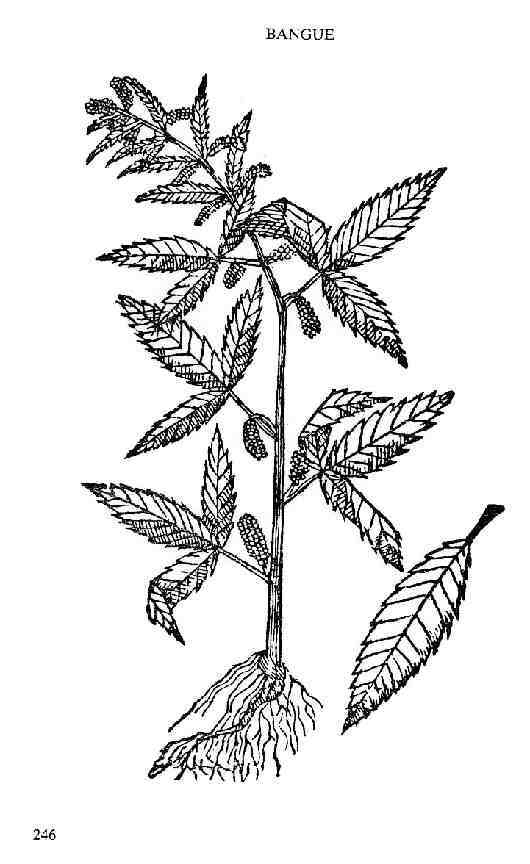

Illustration of bhang by Christoval Acosta (c. 1525 – c. 1594), whose drawings have been used in the Colloquies of Garcia de Orta

Bowrey tells us that “beinge of a more pleasant Operation, much addictinge to Venery, [ganja] is sold at five times the price [bhang] is.” Ganja was often smoked mixed with tobacco, “a very Speedy way to be besotted.” It was also commonly consumed by chewing, he wrote. A search for the term in the Monier–Williams Sanksrit dictionary yields gṛñjana (गृञ्जन), defined as “the tops of [Cannabis] chewed to produce an inebriating effect.” The practice of chewing cannabis (i.e., bhang) was known among qalandar dervishes of this era as far west as Anatolia. Likewise, the semi-legendary Nath Siddha Goraknath features in Tamil folklore as an inveterate chewer of bhang. Conceivably, the sinsemilla technique may have originated substantially prior to the tobacco era as a means of producing seedless inflorescences for chewing – an East Indian refinement of an older custom. The Ānandakanda states cannabis can be taken with betel leaf. Perhaps ganja was an ingredient in paan mixes along with betel leaf and areca nuts. Certainly by the time Pierre Sonnerat arrived at Pondicherry in the 1770s, ganja cultivation was well-established on the Coromandel Coast and presumably the rest of tropical India, as was tobacco cultivation. Based on James Mallinson’s reckoning for the Ānandakanda of circa fifteenth century, that could give a period of two or three hundred years in which ganja was principally a chewed product before tobacco catalysed a widespread smoking culture.

Ganja domesticates (i.e., true var. indica) appear to have diverged from bhang domesticates due to selective pressure for potent and refined aromatic inflorescences—their strong odour “resembling somewhat that of tobacco”, as Lamarck noted of Sonnerat’s specimen. The ganja landraces cultivated in contemporary Aceh are overwhelmingly more “intoxicating” than the crop cultivated for bhang in regions such as Punjab. My guess is that bhang domesticates represent an older form of Indian Cannabis akin to—and probably closely related to—those of Central Asia. Studies already indicate the cannabinoid ratios of crops from Punjab may be like those of Central Asia. Meulenbeld persuasively argues that in Indian texts the term bhang can only be taken to refer unequivocally to Cannabis from the eleventh century, and that it only features writ large from the thirteenth. As discussed here, the early thirteenth century was when Central Asian Cannabis culture exploded southward and westward out of Khorasan following the Mongol annihilation of ‘Silk Road’ cities such as Balkh, Samarkand, and Bukhara.

From the Scythians to the qalandars, Iranic influences appear pivotal to the evolution of Indian Cannabis culture. Ganja—the true var. indica crop and product—on the other hand, is a uniquely Indic innovation of what was once known as the East Indies, a region encompassing India, Indonesia, and much of mainland Southeast Asia. I suspect a crucial factor in the refinement of such domesticates was their cultivation and selection away from wild-growing weedy populations, a problem faced by farmers in Bengal, which abuts the Himalaya, but not in Aceh, which has the added advantage of excellent terroir.

McPartland and Small’s new paper is a landmark in Cannabis studies and a crucial document for any collector, whether amateur or academic. Future studies, in my view as an aficionado, would do well to note the significance of bhang crops from regions such as Punjab, Sindh, and Uttar Pradesh, a substantial majority of which may exhibit distinct morphological and phytochemical traits from classic var. indica ganja domesticates. Collection efforts could also focus on Himalayan landraces from Far West Nepal, and on regions of Northeast India where pristine aboriginal var. himalayensis populations may yet exist. As McPartland and Small emphasize, wild-type populations are the essential reservoir of biodiversity.

In short—stop hybridizing—start collecting!

![Tattoos [01] Scythian clan tattoos from Pazyryk in the Altai Mountains, north into the steppe from Xinjiang](https://therealseedcompany.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/xtattoo-line-drawings.jpg.pagespeed.ic_.7tur5rnrzr.jpg?w=150&resize=150%2C180#038;h=180)

Pingback: Nanda Devi: Landraces and Tall Tales from the Himalayas | The Real Seed Company: The Honest Online Source for Cannabis Landraces Since 2007·

Pingback: Do Landrace Farmers Need Modern Hybrid Strains? | The Real Seed Company: The Honest Online Source for Cannabis Landraces Since 2007·

Pingback: Extinction by Hybridization | The Real Seed Company: The Honest Online Source for Cannabis Landraces Since 2007·

Thanks for sharing, very interesting.

Thanks Luke

Pingback: On Indicas & Afghanicas | The Real Seed Company: The Honest Online Source for Cannabis Landraces Since 2007·

Pingback: The Ancient Indian Origins of the ‘Sinsemilla Technique’ | The Real Seed Company: The Honest Online Source for Cannabis Landraces Founded 2007·